Lending Protocols

As you probably know, lending markets are a cornerstone of TradFi and DeFi. In any financial system, lenders provide capital to borrowers in exchange for interest on the loan. Traditionally, banks and financial institutions intermediate this process — they take deposits and lend them out, profiting from the interest rate spread. These money markets offer instruments like loans, bonds or repurchase agreements to facilitate short-term lending and borrowing needs.

So, in DeFi, lending markets replicate the classical functionality, but using smart contracts that will pool funds from lenders and automatically manage loans to borrowers. Of course, this allows lending and borrowing in a permissionless way: anyone with crypto assets can participate without needing to pass credit checks or KYC, and lenders maintain custody of their assets except when locked in the contract.

During this introduction, we'll explore how DeFi lending differs in requiring collateral, how interest rates are determined, and the risks and mechanics involved.

Overcollateralized vs. Undercollateralized Lending

One major difference in DeFi lending is the prevalent use of overcollateralization. In DeFi, loans are typically overcollateralized, meaning a borrower must deposit collateral worth more than the loan they take. For example, a DeFi platform might require a user to deposit $ 150 of ETH to borrow $ 100 of a stablecoin. This excess collateral acts as a buffer to protect lenders: if the borrower fails to repay, the protocol can seize and sell the collateral to cover the debt. The concept of overcollateralization is essential in an anonymous system with no credit scores, as it ensures solvency of the loan pool even under volatile market conditions

In contrast, undercollateralized or unsecured lending means the loan value exceeds the collateral value (or no collateral at all). This is common in traditional finance – for instance, credit cards and student loans are extended based on creditworthiness with little or no collateral. Such loans rely on identity, credit scores, and legal enforcement for repayment. In DeFi, true undercollateralized lending is more challenging because users are pseudonymous and there's no built-in credit scoring on-chain. As a result, DeFi protocols initially all adopted overcollateralized models to mitigate default risk.

However, there are certain efforts to enable undercollateralized lending in DeFi. Some protocols use alternative data or off-chain identity to assess credit (for example, requiring proven income or using decentralized credit scores). Others implement credit delegation, where one user's collateralized borrowing power is delegated to another trusted party (essentially cosigning a loan). A notable example is Aave's credit delegation feature, which allows a user with collateral on the platform to authorize another user to borrow without posting collateral, under agreed terms. Also, flash loans (covered later) represent a special case of uncollateralized loans that are safe for the protocol by design – they must be repaid within the same transaction. While undercollateralized DeFi lending is still nascent, it's seen as a "next frontier" as protocols find ways to incorporate credit risk assessments on-chain

Some of the keys

Whether overcollateralized or not, DeFi lending platforms share some key components that govern how loans work:

Collateralization Ratios and Borrowing Limits

Collateralization ratio is the proportion of collateral value to loan value, usually expressed as a percentage. It is calculated as:

This metric will indicate the buffer a loan has before it becomes undercollateralized. For exmaple, a ratio of means the collateral is worth 1.5x the outstanding debt. Higher collateralization ratios imply lowr risk for the lender, since more collateral is available to cover the loan.

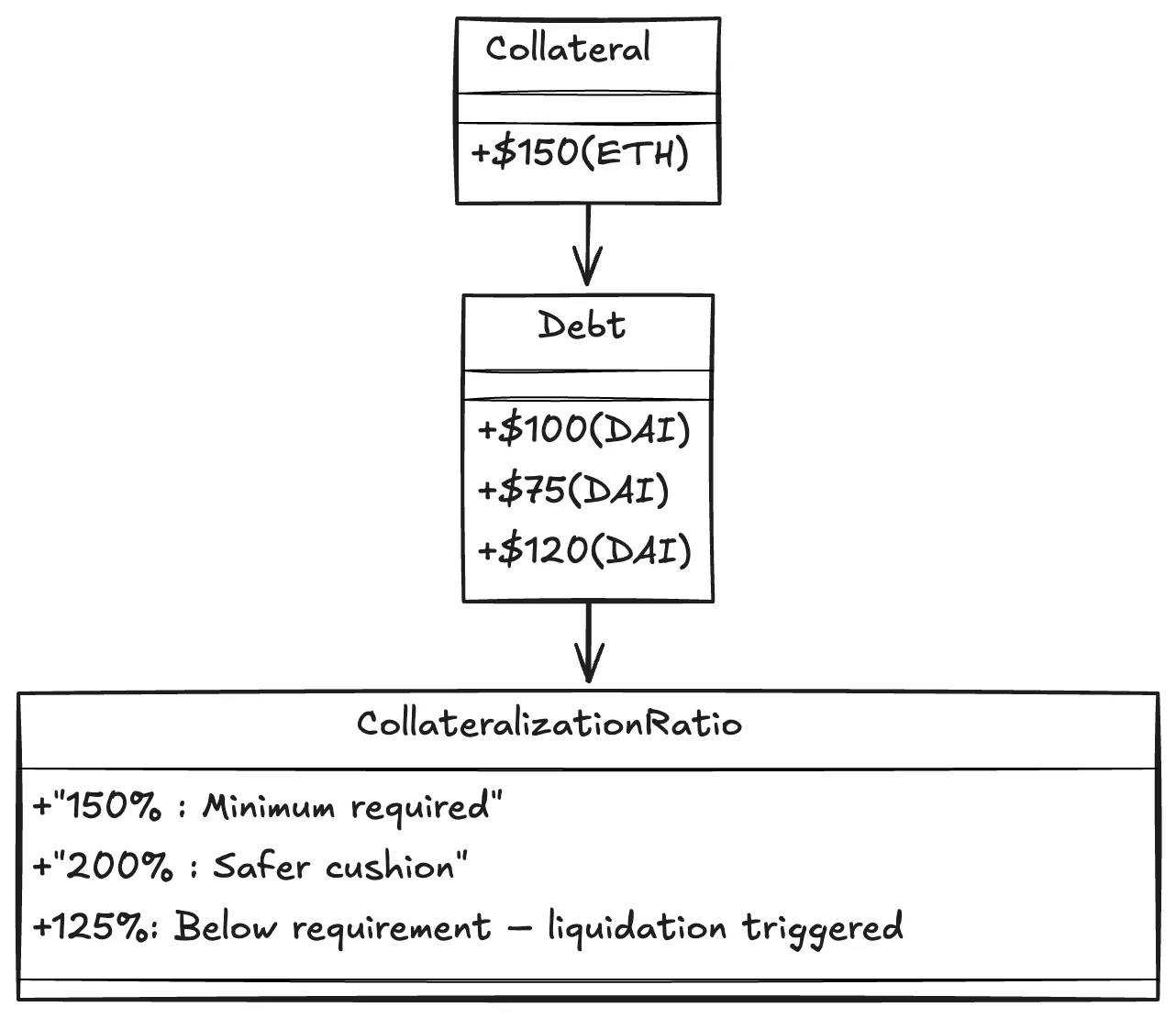

En general, the protocols will enforce a minimum collateralization ratio —or a maximum loan-to-valuo (LTV). When a user supplies assets to borrow against, the platform will only allow borrowing up to a certain percentage of the collateral's value – this is the borrowing limit. For instance, if a platform sets a 150% minimum ratio (which corresponds to ~66% max LTV), depositing $150 of ETH would allow at most a $100 loan. If the user tries to borrow more, the loan would not meet the required collateral ratio and the transaction is not allowed. Different assets have different required ratios depending on their volatility and risk (stablecoins often have lower requirements, while volatile tokens need higher collateralization).

For example, on MakerDAO —now Sky protocol—, the standard collateralization ratio was 150%. If you deposit $150 of ETH in a vault, you can generate up to $100 of DAI (that's a 150% ratio). On Aave, each collateral asset has a specified Loan-to-Value (LTV); for example an 80% LTV on ETH means you can borrow up to 0.8 USD of stablecoin per 1 USD of ETH collateral. In practice, safe borrowers leave a buffer and do not borrow the absolute maximum.

As How to DeFi advises, you should not draw out the full loan allowed by your collateral – maintaining some margin reduces the chance of liquidation if the collateral's price fluctuates.

Example collateralization scenarios for a $150 ETH deposit. Borrowing $100 yields a 150% ratio (at the threshold). Borrowing less ( $75) improves the ratio to 200%, reducing liquidation risk. If collateral value falls to $125% (e.g. due to an ETH price drop to $125 while $100 debt remains), the position is undercollateralized and can be liquidated.

Liquidation Mechanisms

Liquidation is the process by which a loan that falls below the required collateral ratio is partially or fully repaid by selling the collateral. In DeFi lending, if the value of a borrower's collateral drops too much (or their debt increases relative to collateral), the protocol will declare the loan undercollateralized and liquidate it. This is typically automated: anyone (known as a liquidator) can call the smart contract to trigger a liquidation on an unhealthy loan.

When a liquidation happens, the liquidator usually pays off some or all of the outstanding debt on behalf of the borrower. In return, the liquidator receives an equivalent value of the borrower's collateral at a discount – this discount (and often an extra fee) is the liquidation incentive for third parties to step in and clear bad debt. The borrower thus loses a portion of their collateral, more than the debt repaid, which serves as a penalty for falling below the required ratio.

Each protocol has specific liquidation parameters:

- Liquidation threshold: the collateral ratio at which liquidation can occur (e.g. 150% in MakerDAO, or asset-specific in Aave – if an asset's LTV hits its threshold, typically a bit above the max LTV, liquidation triggers).

- Liquidation penalty: an extra percentage of collateral taken as a penalty (for example, MakerDAO charges a 13% penalty on the collateral; Aave's penalties range by asset, often around 5–15%).

- Liquidation bonus: effectively the discount given to liquidators when buying collateral (often equal to or slightly less than the penalty; the remainder may go to an insurance fund or be burned, depending on the system).

Importantly, DeFi loans typically do not seize all collateral when liquidated if it's not necessary. Protocols will only liquidate as much as needed to restore the remaining loan to a healthy ratio, plus the penalty. For example, instead of a borrower losing 100% of their collateral, a liquidation might sell, say, 50% of the collateral to cover the debt and leave the rest in the borrower's account (minus penalties). This partial liquidation approach prevents borrowers from losing more collateral than needed and helps the protocol maintain stability rather than over-collateralizing the system post-liquidation.

The take away here is that liquidation mechanisms protect lendersw and the protocol from default. They do so by socializing the risk to external arbitrageurs who profit from buying collateral cheap, while borrowers who fail to maintain collateral suffer a financial penalty. The possibility of liquidation (and loss of collateral) is the primary risk for borrowers in overcollateralized DeFi loans, which is why maintaining a buffer above the minimum ratio is so relevant.

Interest Rate Models: Fixed, Variable, and Algorithmic

Another core component of lending markets is how interest rates are determined for loans and deposits. Interest is the price of borrowing money, and in DeFi these rates can be structured in various ways:

- Fixed Interest Rates: A fixed rate means the borrowing rate is agreed up-front and remains constant over the life of the loan. In traditional finance, many loans (like mortgages or bonds) have fixed interest. In DeFi, fixed-rate lending is less common but not absent – some protocols and instruments (like fixed-term lending pools or tokenized debt obligations) offer fixed rates. For example, Yield Protocol and Notional Finance allow users to lock in a fixed rate for a loan or deposit for a set term. Fixed rates provide certainty to borrowers and lenders, but they require someone to take the interest rate risk (often via separate pools or hedging mechanisms). Aave also offers a "stable" interest rate option that behaves similarly to a fixed rate in the short term (though Aave's stable rates can be rebalanced if conditions change significantly).

- Variable (Floating) Interest Rates: Most DeFi lending platforms use variable interest rates that can change over time. Variable rates float based on supply and demand in the market. If there's high demand to borrow an asset and relatively little supplied, the interest rate for that asset will climb; if supply is plentiful and demand low, the rate will fall. These changes ensure that markets clear – higher rates attract more lenders (and discourage borrowing) and lower rates do the opposite. In traditional finance, variable rates might be tied to an index (like LIBOR or central bank rates) and update periodically. In DeFi, variable rates update continuously and algorithmically: every transaction that interacts with the pool will recalculate the current rate based on the latest balances (no human intervention needed)

- Algorithmic Interest Rate Models: As you probably have heard, the term "algorithmic rates" refers to the formula that determines interest rates in real time. Essentially, all the common DeFi money markets (Compound, Aave, etc.) use algorithmic models to set variable rates. These typically rely on the utilization ratio of a lending pool – the percentage of supplied assets that are currently borrowed out. For each asset pool, the protocol defines a relationship between utilization (U) and the borrow interest rate. For example, a simple model might be:

- If utilization is low (few people borrowing relative to supply), interest rate = a low base rate.

- As utilization increases, the rate climbs gradually.

- If utilization hits a target or exceeds a certain critical threshold (near 100% usage), the rate can spike very high to disincentivize further borrowing and encourage new supply

Compound and Aave use a piecewise-linear interest curve: from 0% to an optimal utilization (e.g. 80%), the rate increases modestly (slope1); beyond that, the rate increases steeply (slope2) to penalize exhausting liquidity. These models are often adjusted through governance to find a balance that keeps utilization in an efficient range (so funds aren't idle, but also not fully depleted). The end result is an equilibrium rate set by market conditions: when interest is too high, fewer borrowers will borrow (or more suppliers add liquidity), pushing it down; when interest is too low, demand might increase, pushing it up.

| Utilization | Borrow APR | Supply APR |

|---|---|---|

| 0% | 2% | ~2% |

| 50% | 5% | ~2.5% |

| 80% | 10% | ~8% |

| 100% | 30% | ~0% |

In this example, at low utilization, borrow rates are minimal. As utilization rises, rates increase to balance supply and demand. Lenders' APY is slightly lower than borrow APY because protocols take a reserve cut or spread.

It's worth noting that some protocols and platforms also offer hybrid models:

- Aave's "stable rate" is effectively a quasi-fixed rate for borrowers who prefer predictability; it is set at a higher level than the current variable rate and remains stable unless extreme utilization forces a rebalancing.

- MakerDAO's Stability Fee (interest on DAI loans) is a governance-set rate – it changes only when Maker governance votes to adjust it, not continuously. In that sense, Maker's rate model is manual rather than algorithmic, more similar to how a central bank might adjust interest over time.

- Newer fixed-rate protocols let users lock in a rate by matching them with counterparties who take the opposite side (like a lender locking in yield by effectively shorting a floating rate).

As take aways, fixed rates offer certainty, variable rates offer responsive markets, and algorithmic models underlie most lending protocols to secure solvent, efficient operation. Borrowers must contend with the fact that their interest costs could change over time, while lenders need to understand that their yield comes from these same models and can fluctuate with utilization and market conditions.

How a loan works

To bring the concepts together, let's walk through a simplified example of using a DeFi lending platform:

MakerDAO is now Sky, but we will refer to it as the former for the example.

1. Supplying Collateral: Alice has 1.5 ETH and wants to unlock some liquidity without selling her ETH. She deposits her 1.5 ETH into a lending protocol (e.g. MakerDAO or Aave) as collateral. Let's say the current price of ETH is $100, so her collateral is worth $150 total. The protocol acknowledges this deposit and Alice now has a collateral balance. In a pool model like Aave, she would receive aTokens (interest-bearing tokens) representing her supplied ETH which will accrue interest. In MakerDAO, a vault is created for Alice's collateral.

2. Borrowing Assets: Given the platform's collateralization requirement (assume 150%), Alice can borrow up to $ 100 worth of another asset – she decides to borrow 100 DAI. When she takes this loan, the smart contract issues 100 DAI to her (in Maker's case by minting new DAI against her vault, or in Aave's case by transferring DAI from the pool's liquidity). Alice now has 100 DAI to use freely, and a debt of 100 DAI recorded in the protocol. Her collateralization ratio at loan creation is exactly 150%: $150 collateral / $100 debt = 1.5. She's at the minimum threshold in this example, which is risky – it's usually advised to borrow less. (If Alice were prudent, she might have borrowed only, say, 50–70 DAI, leaving a cushion.)

3. Interest Accrual: Once the loan is drawn, interest starts accruing on the 100 DAI debt. Let's say the stability fee (interest rate) is 5% annually. This accrues continuously – in MakerDAO, the 100 DAI debt will gradually increase over time (or equivalently, when Alice goes to repay, she will owe 100 DAI + interest). In Aave, the borrow rate might be variable; if it's 5% now, it could change by the time she repays. Meanwhile, Alice's supplied ETH might also be earning a small interest if the platform pays interest to suppliers (in Maker, ETH collateral doesn't earn yield; in Aave, if ETH is also being borrowed by others, Alice earns ETH interest).

4. Market Movement – Collateral Value Changes: Suppose a few days later, the market drops. ETH falls from $100 to $80 (-20%). Alice's 1.5 ETH collateral is now worth $120. But her debt is still ~100 DAI (plus a little interest, say ~100.1 DAI). Now her collateralization ratio is $120 / $100.1 ≈ 120%. This is below the 150% requirement, meaning her loan is undercollateralized. The protocol will flag this for liquidation.

5. Liquidation Process: A keeper sees Alice's vault is eligible for liquidation. The bot calls the liquidation function on the smart contract. Let's assume a 13% liquidation penalty on MakerDAO. The bot might pay back Alice's 100 DAI debt to the protocol and in return is allowed to take 1.5 ETH collateral. However, the bot only needs to take enough ETH to cover the debt plus the 13% penalty. Thirteen percent of $120 collateral is $15.6. So roughly, the bot pays 100 DAI, and receives $115.6 worth of ETH (which is the debt $100 + $15.6 penalty worth of ETH). The remaining value of Alice's collateral (about $4.4 worth of ETH in this rough math) could be returned to Alice (in practice, auctions and exact mechanisms vary). Alice effectively loses most of her 1.5 ETH, only a small residual (or sometimes nothing if auction inefficiencies occur) might be left after the liquidation. The 100 DAI debt is now fully repaid (the protocol keeps the 100 DAI the liquidator paid), and the 13% penalty in ETH is split between the liquidator (profit) and possibly the protocol system fund. Alice is left with no DAI debt (it's closed) but also much reduced collateral – she suffered a big loss.

6. Alternatively – Repayment: Let's consider if the market had gone up or stayed the same. If ETH stayed at $100 or rose, Alice's collateral ratio would be >=150% the whole time. She would be safe from liquidation. Suppose ETH rose to $120 (her collateral now $180, ratio 180%). Alice decides to repay her loan to get her ETH back. She needs to return 100 DAI plus whatever interest accrued. If a month passed at ~5% APR, interest might be about 0.4 DAI. So she pays 100.4 DAI (usually by sending DAI back to the smart contract). Once the debt is paid, she can withdraw her 1.5 ETH from the protocol. In Aave, she would return the borrowed DAI (or the equivalent aDAI) and the protocol would unlock her ETH collateral. In Maker, paying off the DAI and the stability fee closes her vault debt and allows her to withdraw the ETH. Throughout the loan, she retained ownership of the ETH (it was just locked), so now she benefits from the price appreciation of ETH as well (which is a key reason someone might borrow instead of selling – to HODL the asset and still get liquidity).

So, our classic flow would be: deposit collateral, borrow, manage the position while interest accrues and collateral value fluctuates, and either get liquidated if the position becomes unsafe or repay to reclaim collateral. You can see why managing collateral ratio is vital – a user like Alice should borrow more conservatively (say 60% of collateral value) to withstand market swings. It also shows how interest and liquidation come into play: interest adds to the debt over time, and liquidation is the fail-safe to protect the system (at the borrower's expense) when things go wrong.

Case Studies!

This was a general introduction, but you should check out the following:

- Aave V2 Whitepaper: https://github.com/aave/protocol-v2/blob/master/aave-v2-whitepaper.pdf

- MakerDAO Whitepaper: https://makerdao.com/en/whitepaper/

We encourage you to write some notes and ask questions about them! What do you think? Do they make sense? Is there any way we could improve them?

References

https://finematics.com/lending-and-borrowing-in-defi-explained/ - Great overview of DeFi lending fundamentals

https://nucks.co/notes/how-to-defi-beginner - Beginner-friendly guide to DeFi concepts

https://blog.chain.link/undercollateralized-lending-teller-deco-poc/ - Deep dive into undercollateralized lending

https://www.coinbase.com/learn/advanced-trading/what-is-defi-liquidation - Understanding DeFi liquidations

https://www.rareskills.io/post/defi-liquidations-collateral - Technical details of liquidation mechanisms

https://www.rareskills.io/post/aave-interest-rate-model - Analysis of Aave's interest rate model

https://www.coinmetro.com/learning-lab/defi-lending-and-borrowing - Comprehensive guide to DeFi lending