Oracles

We all know that blockchains are deterministic environments: every network node replays the same transactions in the same order, ensuring they arrive at a single, agreed-upon state. This underpins decentralized consensus but also means that smart contracts cannot directly connect to external data sources. By design, Ethereum nodes only trust what is already on the blockchain, so any offchain data—such as asset prices, weather reports, or exchange rates—never reaches contracts unless an outside actor “pushes” it onchain.

Oracles exist to bridge this gap. They feed offchain information into the network in a trustworthy manner, whether it’s pricing data for DeFi loans or external event outcomes for prediction markets. Oracles are, however, a potential single point of failure. Under normal conditions, they can appear robust, but in times of extreme volatility weaknesses often emerge. There are many flavors of oracles: software-based, decentralized, centralized, hardware-based, inbound, outbound...

This diversity in designs reflects the various needs of dApps. However, challenges remain: How can we ensure that data is trustworthy and resistant to manipulation? Is full decentralization achievable, or do centralization risks persist? How do we maintain protocol sustainability over time, especially under potential attack vectors? It's important to note that relying on oracles introduces potential risks, referred to as the oracle problem. A compromised or manipulated oracle could feed incorrect data to smart contracts, leading to erroneous execution and potentially catastrophic consequences for the applications and users that depend on them.

If a DeFi protocol needs the price of ETH in USD, it cannot simply call an offchain API from onchain code. Even if it did, that same API might produce different results at different times, breaking the deterministic process that each Ethereum node relies on to maintain consensus.

As a result, oracles must feed external data into smart contracts, but then these contracts effectively “trust” whatever the oracle says. If a malicious actor can control or manipulate the oracle, they can cause really bad outcomes—such as incorrect collateral liquidations or erroneous insurance payouts. Equally important is availability: the best oracle in the world becomes useless if it frequently goes offline or fails to update data as needed. Underlying all these considerations is the question of incentives. Fully decentralized oracles typically rely on independent node operators, all of whom need strong economic or reputational incentives to remain honest, especially if short-term profit could be made by misreporting data.

Common Oracle Design Patterns

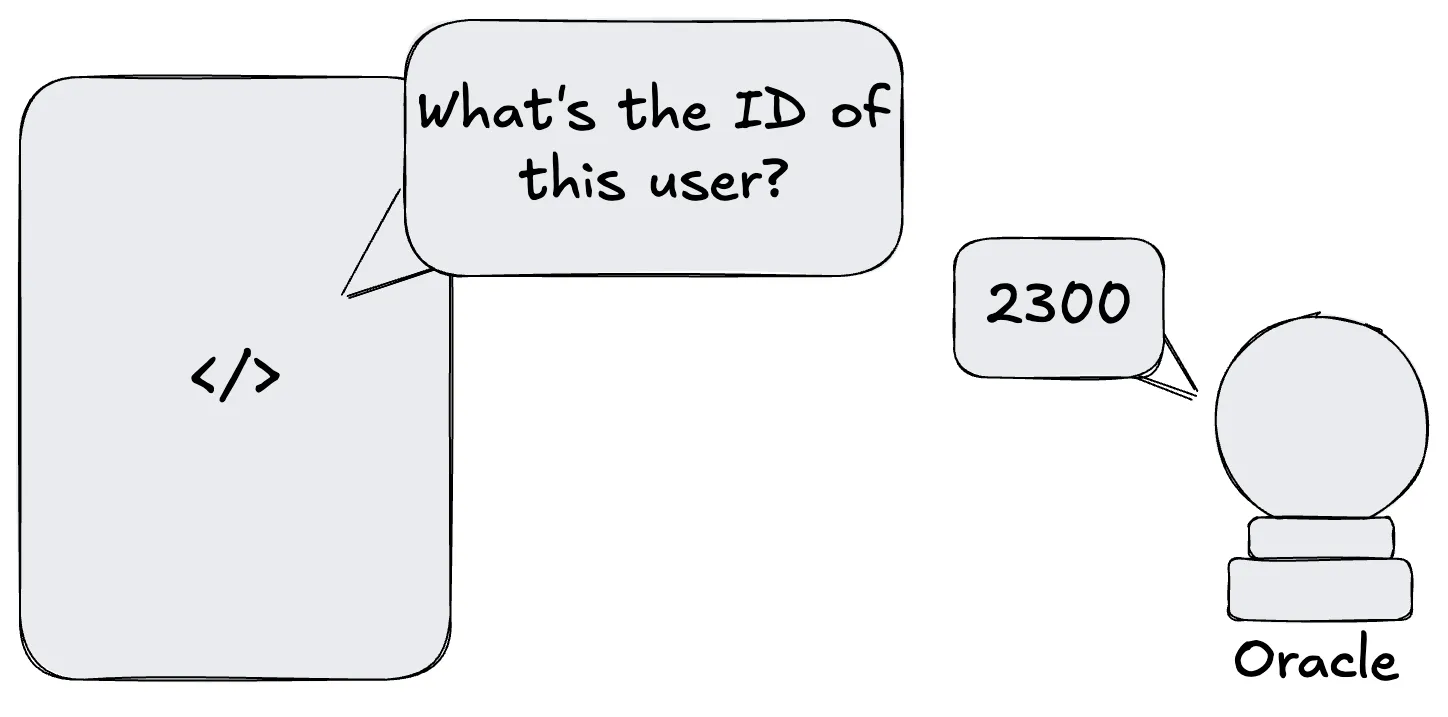

Oracles usually follow one of three major design patterns: immediate-read, publish–subscribe, or request–response. Immediate-read oracles function like static reference contracts, storing data that changes infrequently or can be hashed (e.g., membership credentials or official documents). Other contracts can look up this onchain reference at any time, making it useful for verifying an ID or membership status.

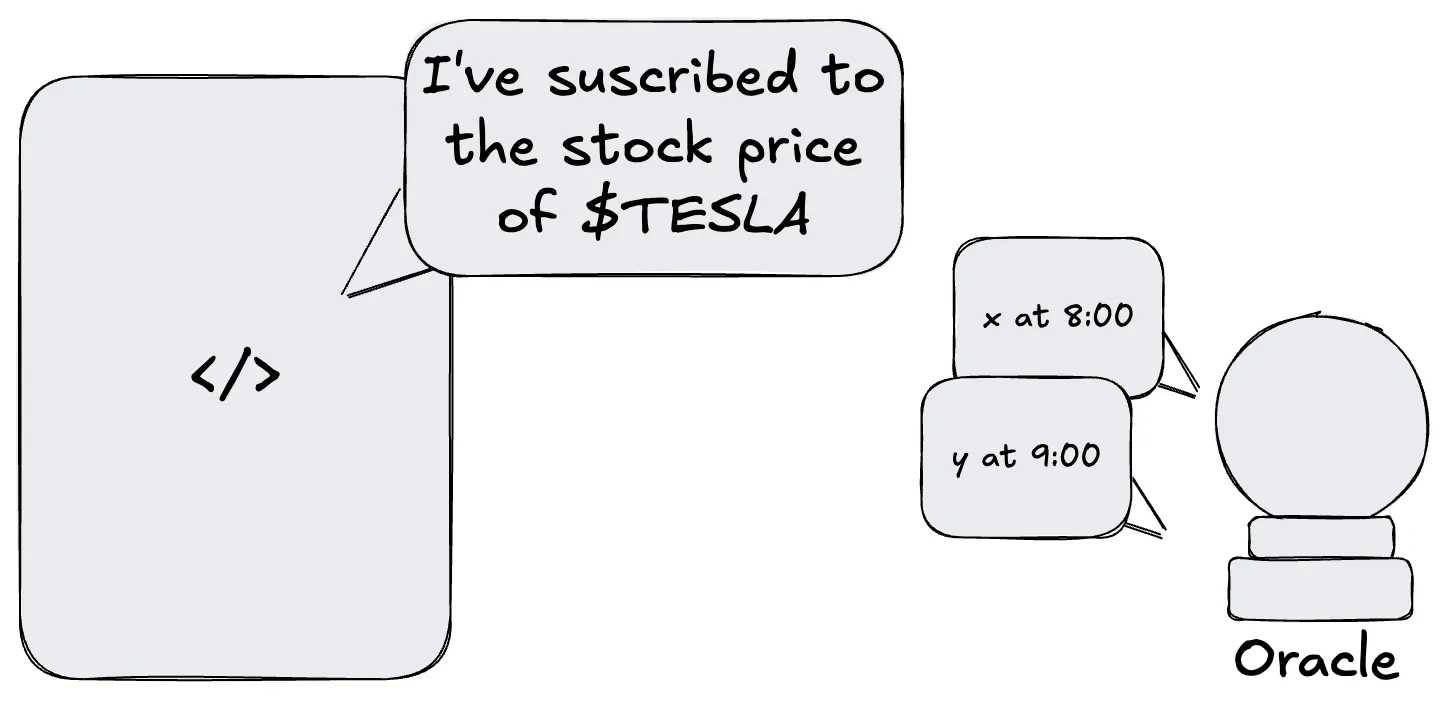

Publish–subscribe oracles, sometimes referred to as data feeds, broadcast new data on a periodic basis. This pattern works well for frequently updated values, such as exchange rates or interest rates, since any smart contract can read the oracle’s updated storage rather than individually requesting it. Many DeFi protocols use Chainlink or MakerDAO’s price feeds in precisely this manner.

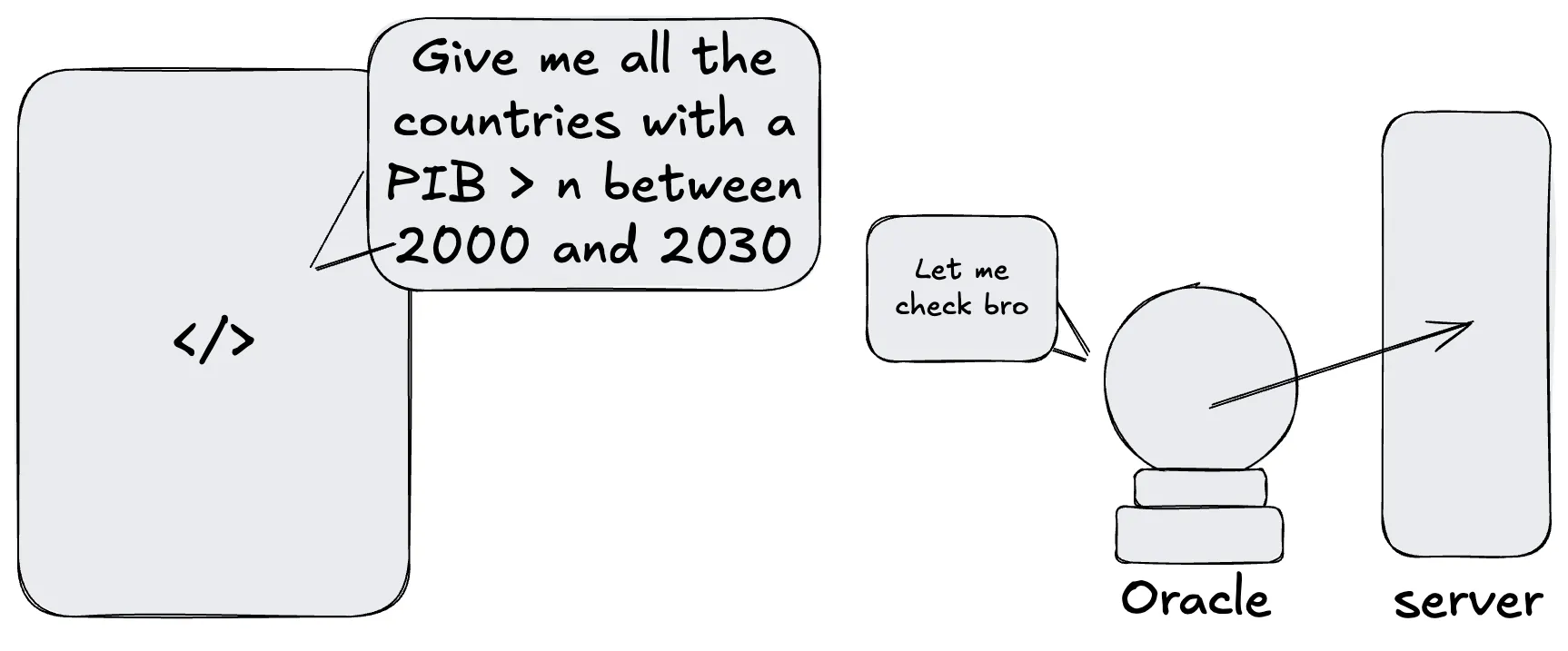

Request–response oracles are designed for situations where a contract wants some offchain data on demand. Rather than receiving constant updates, the contract issues a request specifying what data is needed. Offchain services that watch for these requests then gather the data from external APIs and submit it onchain. This approach is particularly flexible for large or occasional queries but may involve more transaction overhead if used frequently.

Centralized vs. Decentralized

When reviewing how oracles source and relay offchain data, one of the biggest distinctions is whether they are centralized or decentralized. Centralized oracles rely on a single provider to sign data and post it onchain. This model is easy to set up but is vulnerable to a single point of failure: if that provider is compromised, the entire feed becomes untrustworthy.

Decentralized oracles, on the other hand, aim to distribute data-fetching across multiple nodes, each potentially sourcing that data from numerous APIs. The system then aggregates the various inputs using schemes like median voting or staked consensus. This makes a successful manipulation more difficult, as it would require collusion among many nodes and possibly many data sources. However, decentralized oracles can be more expensive to operate, since each node must be incentivized to fetch data and post it onchain. Some solutions incorporate trusted execution environments (TEEs), such as Intel SGX, to show that data was fetched in a secure enclave, but TEEs themselves can experience vulnerabilities or exploits. In reality, no approach is perfect, so teams often blend multiple methods to minimize risk in different ways.

Key Security & Attack Vectors

We already discussed this, but security is really relevant for oracles, especially when billions of dollars in user funds rely on them. One clear threat is the classic single point of failure: if a protocol depends on just one data provider, the entire system is at risk if that provider turns malicious or is forced offline. Sybil or collusion attacks pose a similar hazard in so-called “decentralized” networks where, in practice, a single entity could control a majority of the oracle nodes. Even multiple honest nodes can be undermined if their singular data source is compromised, leading to uniformly incorrect onchain values.

A more subtle threat arises from Ethereum’s switch to Proof of Stake, which occasionally allows the same block proposer to mine multiple blocks in a row. An attacker could exploit this by manipulating the exchange rate on a DEX in block , skipping arbitrage transactions, and finalizing an inflated or deflated price in block . Oracles that rely heavily on short-term (time-weighted average price) data can be tricked if no honest actor intervenes in time.

Incentive mechanisms are meant to mitigate these risks. Many decentralized oracles require node operators to stake tokens; if they diverge from the consensus or post corrupted data, the system slashes their stake. Others employ reputation scores or commit–reveal schemes to prevent freeloading and collusion. Ultimately, oracles remain a prime attack surface, especially under the stress of black swan scenarios, where normal assumptions may not hold up.

The Status Quo

Chainlink is the most widely adopted oracle provider in DeFi. It aggregates data from numerous node operators, achieving a degree of decentralization. However, critics note that the node incentives themselves remain centralized, partly because Chainlink subsidizes them via a multisig that can release LINK tokens. Some worry that, if these subsidies end or become politicized, node operators could lose incentive to maintain accurate feeds. Chainlink has served as a critical backbone to many DeFi protocols, though, and it remains the go-to solution for most teams.

MakerDAO’s —now Sky—oracle system, used to price collateral for DAI issuance, was also popular. It enlists a set of whitelisted feeds and aggregates their data onchain, but smaller protocols may find Maker’s approach too expensive to replicate, given the amount of gas usage and the number of trusted reporters involved. Meanwhile, Uniswap v3 introduced an onchain TWAP oracle. By relying on their liquidity pools, protocols can look up asset prices without an offchain aggregator. While this is elegantly decentralized, it can be prone to “liquidity unpredictability”: the pool’s liquidity might change drastically, and, under certain conditions—such as multi-block PoS exploitation—this data can be manipulated.

Example: A Basic Request–Response Oracle

Let’s think of a simple contract that holds a function like createRequest(url, key). Once a user (or another contract) calls this function, the contract emits a NewRequest event, which offchain services monitor. Suppose multiple node.js services see this event and each one fetches the JSON data from the specified url, extracting the field corresponding to key. Each service calls back updateRequest on the Oracle contract with the result they fetched. The contract tallies these responses, and if enough identical answers come in (say two out of three match perfectly), it finalizes that as the consensus result, triggering an UpdatedRequest event.

This pattern is quite flexible because any JSON endpoint can be queried. However, in the face of malicious or unavailable data sources, or if all offchain services rely on a single compromised API, the consensus mechanism doesn’t help much. As a result, even “simple” oracles like this require careful design to avoid reliance on one data provider behind the scenes.

Oracles are reliable until they’re not

While many DeFi users trust solutions like Chainlink or Maker or rely on a Uniswap-based TWAP feed, these systems can collapse in rare, high-stakes moments. For instance, if Chainlink’s underlying node incentives fail because the multi-sig can’t or won’t continue subsidizing node operators, the entire chain of data might degrade. Maker invests heavily in gas incentives and whitelisted feeders, which is viable for an $8B platform but not necessarily for smaller protocols. Meanwhile, Uniswap’s v3 oracle is elegantly sustainable but difficult to predict when liquidity providers can remove liquidity at will. Further, the new proof-of-stake environment enables block proposers to skip arbitrages for multiple consecutive blocks, amplifying the risk of short-term price manipulation.

The overarching moral is that conventional solutions work fine day to day but can run into serious issues during black swan events—those rare but cataclysmic moments of extreme volatility or abrupt market shifts. Oracles must be resilient enough to withstand those events if they are truly to be considered trust-minimized.

Price

To address these concerns, some years ago we developed Price, an oracle solution that is based on Uniswap v3 but introduces certain safety measures to offset liquidity unpredictability and multi-block attacks. First, Price requires a pool seeded with a “full-range” position of liquidity, ensuring the oracle feed won’t vanish suddenly if LPs exit. Part of the fees earned by that pool goes back into maintaining the oracle’s operational security, such as paying gas for keepers or building up the cardinality needed for more precise calculations.

Second, Price applies a short delay—two minutes, for instance—along with an automated job that detects suspicious spikes in price or volume. If these signals indicate a potential multi-block exploit, the job corrects the observation array, effectively filtering out the attack data before a short is finalized. This design attempts to remove the possibility that a block proposer can single-handedly manipulate prices across consecutive blocks without arbitrage transactions intervening.

It is entirely permissionless—any user can add a WETH–TOKEN pair to bootstrap a new feed. Because it uses the existing Uniswap framework, it inherits that ecosystem’s decentralization rather than relying on a single company or multi-sig to subsidize node operators. No additional token is minted to finance or control the system, eliminating a potential incentive mismatch. In essence, Price aims to balance three fundamental objectives: reliability, decentralization, and sustainability.

This is a brief introduction, you should dive into oracles and their design checking the resources 👇

Resources

Ethereum Oracles Documentation